Cracow Saltworks Museum in Wieliczka

The Museum is a state-owned, independent, scientific, research and educational institution, subject directly to the Polish Ministry of Culture and National Heritage.

The initiator of establishing the museum was Alfons Długosz – Polish painter, teacher and social activist living in Wieliczka. The directors of the local salt mine, who in the 1950s planned to liquidate many of the workings, granted their consent on his exploration and collection of old tools, devices and mining machines to protect them from destruction. The objects gathered from the excavations made up, as early as in December of 1951, the first exhibition, organised by Alfons Długosz in the Warsaw Chamber and open for visitors. In the years to come, Alfons Długosz’s collection was expanded on and he acquired 14 post-excavation chambers for the purposes of their exhibition, all located on the 3rd level of the mine, at the depth of 135 m underground. Repair and adaptation works of the chambers were finalised by Polish Ministry of Art and Culture. By the Ministry regulation of 23rd March 1961, the exposition was transformed into an independent central museum. Owing to the support and financial aid from the state, one of the most modern mining exhibitions could be organised in the Wieliczka salt mine. Moreover, it was then the biggest mining museum in the world. Practically all issues related to the Cracow Saltworks Museum, organised chronologically or thematically, were presented. Next to geological, archaeological and historic exhibition, there was a most valuable, and unique on a world scale, collection of wooden hauling machines from the 16th-19th c. The underground Cracow Saltworks Museum exhibition became available for visitors in 1966 on the occasion of the 1000th anniversary of the Polish state. In the following decades, further 3rd-level workings, presently taking up the space of 7.5 km2, were adapted for the purposes of the museum exhibition. It features about 2500 original pieces.

The seat of the museum is the Saltworks Castle in Wieliczka, located near the salt mine. The oldest castle buildings date back to the 13th c. Middle Ages-origin can be ascribed to the Central and Northern Castle, towers, walls and saltworks kitchen. From the beginning of its existence up to 1945, the castle was the seat of the management of the Cracow Saltworks, i.e. the salt mines in Wieliczka and Bochnia, saltworks, craft workshops, warehouses and magazines. Until 1772, the Cracow Saltworks, including the Castle, was the property of Polish Kings and it was managed on their behalf by mine administrators. Between 1772 and 1918, the Saltworks belonged to the Austrian House of Habsburg, and since 1918 up to this day – to the Polish state. Throughout the centuries, the castle was redeveloped and expanded. It was devastated by fires and raging wars. The last serious damage was dealt by the World War II. Following 1945, the castle buildings housed healthcare facility and a kindergarten. Owing to the striving of the Cracow Saltworks Museum and the financial aid granted by the Ministry of Art and Culture, in 1976 building and renovation works were commenced, which would restore the castle to its former look and significance. The works were completed only in 1996. In the meantime, next museum exhibitions were organised and open for visiting in the Castle: archaeological one, one devoted to the history of Wieliczka, and the most precious salt cellars collection in Poland. The building is the place of storage of an invaluable collection of historic books and mining maps, as well as saline archive, handed over to the museum by the salt mine. Saltworks Castle was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2013.

Cracow Saltworks Museum employs presently over a hundred people – specialists in various fields. According to its charter, the Museum business activity involves the Cracow saltworks, i.e. the salt mines in Wieliczka and Bochnia together with Subcarpathian saliferous terrains and other salt mines, both operational and fully exploited. The range of subjects and the time-frame of the Museum employees’ research works are extensive and diversified. Geological studies concern Miocene (the origin of the salt deposit), and the archaeological – the Neolithic (beginning of the settlement and salt evaporation industry in the region). In the domain of history and immaterial culture, the range of research covers the period between the 13th c. and the end of the 20th c. It concerns the development of the salt mining and salt evaporation technology, the role and significance of the salt business in the history of Poland, mining towns, art and ethnography. One of the essential tasks of the museum is the preparation of studies on history and conservation for protective works on the historic excavations in the “Wieliczka” and “Bochnia” Salt Mines; another is issuing opinions and conservation permits regarding these areas. Additionally, the museum is still collecting, preserving, cataloguing cultural goods, and making them available for visitors in permanent and temporary exhibitions. Apart from that, it engages in intense publishing activities (academic publications, albums, guides, catalogues, monographs). In museum, a special attention is paid to educational activities, encompassing Wieliczka and the surrounding communes, including Cracow. Educational classes, workshops, lectures, contests and open-air events are organised for children, the youth and adults. The Annual “Feast of Salt” draws thousands of participants to the Castle. The Museum maintains a close cooperation also with other museums, research facilities and universities from the country and abroad, and takes part in international projects. In the years to come, it is planned to expand on the castle exhibition surface and arrange new temporary and permanent exhibitions. It will be possible owing to a successful acquisition of a new building, located right next to the salt mine, moving museum offices to it and a further adaptation of the castle rooms.

The “Wieliczka” Salt Mine S.A.

The mine is a sole shareholder state joint-stock company, coming under the Polish Ministry of Energy. It follows on the activities of the company which has operated continuously for almost 750 years. Presently, the main focus of the company is the preservation of monument – securing the world-unique mine workings, mitigating natural risks, systematic decommissioning of the non-heritage section of the mine, and conducting commercial tourism activities.

The salt deposit present in the Wieliczka area was formed approx. 13.6 million years ago, in a shallow Miocene sea. It runs from east to west in a narrow band reaching 10 km in length, up to 1.5 km in width, and is located relatively shallow below the surface of the earth. Thousands of years ago, the upper layers of the deposit were exposed as a result of leaching, in the form of brine springs. Human occupants of the area started to exploit the springs as early as in the Middle Neolithic (3500 BCE). Signs of settlement and organised production of evaporated salt were left on this area by subsequent communities from the Bronze and Iron Ages, as well as from the Roman and the early Medieval periods. Already by the 11th-13th century, Wieliczka was a salt evaporation centre well-known in Poland and in its neighbouring countries under the proud name ‘Magnum Sal’ (Great Salt). The salt workers’ settlement was soon seen to grow into a small town. Trade and manufacturing practices flourished, and in 1290 the town was granted the urban charter.

A breakthrough came about in the second half of the 13th century, when rock salt was found in the Wieliczka area. First extraction shafts were erected then in the modern-day town centre. The salt evaporation and extraction were soon entirely taken over in this area by Cracow dukes – and later on by Polish kings. Already in the 13th century, the Wieliczka company became merged with a similar undertaking in Bochnia, 30 km distant. This resulted in the creation of the Cracow Saltworks, which operated in this form until 1772. Throughout this period, it remained the largest manufactory in Poland, and one of the largest in Europe. The Crown Treasury during the Medieval times would see up to a third of its income coming from the Saltworks. The Polish kings funnelled revenues from the ‘white gold’ into maintaining the court in Cracow, paying wages of their officials, construction of castles and churches, as well as the founding the first Polish university. The emerging organisational structure of the saltworks was codified in the ‘Statute’ issued by king Casimir the Great in 1368. The statute enshrined in law the old practices, while establishing new regulations aimed at improving efficiency and increasing revenues from the saltworks. They defined rules for salt making and for mining the rock salt, and regulated miners’ labour and salt trading terms.

In the early history of the mine, all work was done by hand, using very simple mining technique. Starting with the half of the 14th century, the Regis shaft became the main extraction shaft. The few accompanying shafts from that period no longer exist. All shafts were at most 50-60 metres deep, reaching the first level of the mine. Underground, the diggers would use pickaxes to make corridors in search of clusters of salt fit for extraction. Once a salt lump or salt bed was found, the extraction work would begin. The miners would start by using iron wedges to separate rectangular (vertical and horizontal) salt blocks from the walls, before breaking them into smaller, cylindrical or barrel-shaped lumps, so-called ‘loaves’, each weighing from 300 kg up to 2 tonnes. Salt pieces and loose salt were also mined by diggers and loaded by them into barrels. Another group of labourers – the haulers – would carry loose salt in niecki (type of basin) and płochy (backpacks made of lime tree bast or hemp), while barrels were transported to the shaft on wooden sledges (szlafy). Loaves were rolled with the use of beech clubs. Once at the shaft, they were taken to the surface using hemp ropes or ropes made of lime tree bast. The ropes were attached to the drums of manually operated cross-shaped winches and hoists. In the middle of the 15th century, the miners started to employ horses – the animals were harnessed to large wooden hoists, so-called Polish-type treadmills, which were mounted on the earth’s surface, at the mouth of a shaft. The mills were covered by protective structures with conical roofs. Beginning in the 16th century, horses would also work underground, pulling sledges with salt along mine galleries.

Apart from salt mining, work on securing and draining the mine was taking place from as early as the 14th century. In order to protect the workings from collapsing, simple wooden supports were being erected, as well as larger wooden structures called cribs. As for water, it was collected into ducts running along the mine workings and drained into sumps at the bottom of the shafts. From there, it would be hoisted to the surface in cebry (wooden buckets to carry the water) and bulgi (cow leather waterskins). The Wodna Góra shaft was erected below the Saltworks Castle in the first half of the 14th century, just for the purpose of draining the mine. The brine would be transported from the shaft via a duct system, to the nearby saltworks, so-called karbaria. Up until 1724, evaporated salt remained a very important part of the overall salt production activities in Wieliczka. For almost four centuries, the sales revenues from that branch of production were used to cover the costs of rock salt mining. From as early as at the end of Medieval period, the mine in Wieliczka would begin to attract the attention of contemporary humanists, scientists, artists and aristocrats. Presumably in 1490 the mine was visited by Konrad Celtis and in 1493 by Nicolaus Copernicus. However, up until the 17th century, visiting the mine as a guest was restricted to special occasions, and required personal permission from the Polish king.

The mine entered a stage of rapid expansion in the 16th century. New shafts were established: Boner, Bużenin, Lois, Lubomierz. Extraction works below level 1 were initiated, while examination through underground fore-shafts was conducted. The mine was employing a few hundred people and had an annual yield of approx. 16 thousand tonnes of rock salt. In the 17th century, additional shafts were erected, including: Górsko, Janina, Ligęza, Leszno, Boża Wola. Between 1635 and 1642, the Daniłowicz shaft was established, through which salt deposits were exploited in the area of the modern-day tourist route. In the same shaft brave tourists could be lowered into the mine in special seats (szlągi) attached to the rope of the treadmill. A more comfortable mode of descent was provided for high-status visitors to the mine in the second half of the century, in the form of winding stairs in the new Leszno shaft, replacing ladders. However, the stairs collapsed towards the end of the 17th century. Kilometres of new underground corridors were built, and exploitation of the second level of the mine was already under way, at the depth of approx. 100 metres. Also, treadmills started to be used underground, as a means of transporting the excavated salt through fore-shafts from lower parts of the mine. At the end of the century, some workings turned into vast chambers, reaching 20 metres in height (modern-day chambers of Mikołaj Kopernik, Kazimierz Wielki, Pieskowa Skała, Drozdowice, Michałowice). However, little care was given to securing the depleted workings. Chamber collapses were not unheard of, creating sink holes in the town above and leading to loss of life and property. Methane explosions and fires were also occurring, including the disastrous fire in the Boner shaft in 1644, which would rage in the mine for the next 8 months. The shaft top and wooden securing works were consumed by the fire, causing cave-ins and sink holes. 20 miners died. The second half of the 17th century was a period of economic decline of the Saltworks, stemming from poor financial situation and outdated production organisation. In accordance with the requirements of royal grants, generously awarded over the centuries, a large part of the produced salt had to be sent free of charge to numerous institutions of the Church, as well as to secular recipients, not providing any income to the Saltworks. The mine stewards would sometimes fail to fulfil their obligations towards the king. As a result of wars and civil unrest rampant in Poland, there was a collapse of the salt trade.

The rule of the Saxon House of Wettin dynasty in Poland (1697-1763) brought to the Saltworks the much-needed reforms and improvements. The stewardship over the mine was taken over by mining specialists from Saxony, introducing new technological thought and work organisation. Extraction shafts were extended to deeper levels, new types of treadmills, so-called Saxon-type horse gears, were implemented and new maps of the workings were drawn. Gunpowder started to be used for blasting galleries. Also introduced were new methods of drainage, ventilation and securing of workings. Around that time many of the mine chambers were decorated with late-baroque reliefs, ornaments and statues. Underground chapels were also erected. The practice of salt evaporation from brine in outdated saltworks located next to the shafts was abandoned. The reforms of the Age of Enlightenment were also applied to the miners. Work safety regulations were implemented, together with fire control instructions. The annual salt output reached approx. 40 thousand tonnes, and the mine became much more profitable thanks to the Saxon administration improving salt sales and trade across the country. Once again, the mine became an important mining centre, to which such mining academies as Leoben (Austria), Příbram (Czech Republic) or Banská Štiavnica (Slovakia) would sent their students and graduates for obligatory training.

The 1st partition of Poland in 1772 brought the Polish royal rule over the Cracow Saltworks to an end. The mine stewardship was taken over by the General Office for the Saltworks with its administrator, representing the Habsburg Monarchy. New drawing and descent shafts were constructed (the Cesarz Józef shaft – the modern-day Kościuszko shaft; the Cesarz Franciszek shaft – the modern-day Paderewski shaft; the Cesarzowa Elżbieta shaft – modern-day the Święta Kinga shaft). On the other hand, the existing shafts were extended down to levels 3-6 of the mine, or decommissioned. The Hungarian-style treadmills introduced at that time were capable of hoisting 2 tonne loads in one go, from the deepest parts of the mine. Hemp ropes for use with these treadmills, 200 fathoms long (360 metres), were made in a rope manufacturing facility, located in the neighbourhood of the modern-day railway line. The workings dug at that time using the blasting method could reach sometimes huge sizes (e.g. the modern-day Staszic chamber reached the height of 50 metres). These workings were secured with wooden cribs, pillars and timbering. The Austrian administration from the beginning was deeply interested in developing tourism in the mine. As early as in 1774 a tourist route was created, running through 28 of the most presentable chambers of levels 1 and 2, and the ‘book of strangers’, i.e. a registry of visitors, was established. The tour was 3-hours long and would normally attract representatives of European royal houses, aristocracy, officials, church dignitaries, prominent artists, scientists and travellers. The sightseeing was accompanied by music, shows of fireworks, and included watching miners at work. In the 19th century, the visitors included e.g.: Frédéric Chopin, J.W. Goethe, Dmitri Mendeleev. The visitors number towards the end of the 18th century oscillated around 120 persons per year. By the end of the 19th century, it was approx. 4000 per year.

The mine in Wieliczka saw a technological breakthrough only in the second half of the 19th century. In 1861 the first steam-powered winching machine was installed in the Regis shaft top (almost 100 years after the invention of steam engine by James Watt). Over the next 20 years, all of the battered horse-powered treadmills were replaced with steam machines. The wooden roofs over the treadmills disappeared from the town landscape, replaced by brickwork shaft tops and boiler rooms. The shafts started to be equipped with steel ropes and elevator cages for transporting people, horses and materials. The year 1861 witnessed in the mine the introduction of iron carts on rails, pulled by horses, resulting in significantly improved efficiency of underground transport. The miners started to use manually-operated drills. Salt was exploited by blasting, with the main product taking the form of crushed salt, produced in salt mills. Rail tracks were laid between the shafts and the Wieliczka railway station, and from 1889 steam locomotives replaced horses in pulling rail cars loaded with salt. By the end of the 19th the century, annual salt production reached 140 thousand tonnes. Salt sales were managed by the Imperial-Royal Sales and Distribution Office. However, a few of the magnate families from Wieliczka also managed to profit from wholesale salt trading (Commercial Salt Company) – these profits included elevation to aristocracy and a number of palaces, beautifying the Wieliczka landscape. The Wieliczka town was growing and changing. In the 1830s an idea emerged to transform Wieliczka into a state-of-the-art balneotherapy spa. A bathing centre was built near the mine, making use of the therapeutic qualities of the mine water. The facility included bathhouses, a sauna for inhalation therapy, a brine drinking fountain, guest rooms and a theatre. In the second half of the 19th century, the Park of St. Kinga was constructed – an interesting composition with a pond, and an open theatre where the salinary orchestra would play. The saltworks administration was also taking care of the miners. The mine employees enjoyed the access to their own hospital, free medication from the saltworks pharmacy, and retirement coverage for themselves and their families. Miners’ children attended kindergartens ran by nuns and financed by the mine. Later, they could attend the Mining School, established in 1861. Brickwork housing projects were built for the miners, as well as bathhouses for their use – free of charge. The saltworks administration issued the miners with work clothing and parade uniforms with accessories.

The beginning of the 20th century was a time of further changes in the mine. New expanded shaft tops were constructed (the Święta Kinga shaft, the Daniłowicz shaft), as well as steel winching towers. The shafts reached down to level 8 of the mine, i.e. almost 300 metres deep. The mine initiated leaching exploitation of the workings by leaching the deposit with water, at first with the wall spraying method, later on by borehole leaching and chamber leaching. Between 1910 and 1913, a very technologically advanced – for that time – vacuum saltworks facility was constructed in Wieliczka, which processed brine produced in the mine underground, and next in a new borehole mine in Barycz. During the 1920s, the annual output of the Wieliczka mine was at the level of 100 thousand tonnes of salt. The electrification process was started before the WWI erupted. In 1912, the first electric winching machine in Wieliczka was installed in the Regis shaft top. From the 1918, electric lighting started appearing in the workings of the mine, replacing the centuries-old practice of using candles, tallow cressets, oil and carbide lamps.

The 1918 was, however, mainly the year of another historical change in the mine. Poland regained independence, and on 1st of November, the Polish Liquidation Commission in Cracow, established at the initiative of Polish representatives to the Austrian senate, took over the Cracow Saltworks. A number of shafts, chambers and galleries were renamed. The Polish administration headed by the headmaster – later by the director – continued the electrification process. Miners began to use pneumatic drills and cutters. Artificial ventilation system was installed in the entire mine (downcast and upcast shafts equipped with suction fans) and pneumatic pumps to drain the workings. Battery-powered locomotives introduced in 1925, and later on traction line-powered ones, gradually started to replace underground horse-powered transport. Voids left underground in mined-out workings started to be backfilled with sand brought in from the surface. The impressive Św. Kinga shaft top hosted a lamp storeroom, a guildhall, and a mining rescue station. It became the primary shaft for transporting miners and materials down into the mine.

Fortunately, the tragic period of WWII did not substantially harm the Wieliczka salt mine. In 1939, the German army occupied the mine and the extraction continued. In 1944, Germans set up an underground armament factory in the mine, but it functioned for a few months only. In the January of 1945, the mine came under control of the Soviet Red Army, which soon after transferred the company to the new communist government. The mechanization and electrification processes were finalized under Polish administration. In 1961, an electric winching machine and a four-level elevator with 36-person capacity were installed in the Daniłowicz shaft. Between the 1950s and 1990s, the Wieliczka mine expanded, reaching 245 km of galleries on 9 levels, 327 metres deep, with 2391 chambers, 26 listed shafts, and 180 fore-shafts connecting the levels of the mine. In 1964, dry method of rock salt extraction ended. However, leaching the chambers allowed the mine to reach its maximum output in 1976: 260,000 tonnes of evaporated salt. However, later on the extraction fell significantly, due to deposit depletion and the resulting unprofitability of further production, as well as due to the mine switching its focus to tourism and services. The Wieliczka salt mine concluded all extraction activities in 1996. The modernized saltworks continue processing brine from natural seepages, with annual yield of approx. 12 thousand tonnes of evaporated salt with the highest purity of all domestic-produced salt (99.99% NaCl).

During the 1960s, the spa traditions saw resurgence. It is where the first in the world underground micro-climate treatments of allergies and diseases of the respiratory system were undertaken. Presently, the “Wieliczka” Salt Mine Health Resort administered by the mine, and certified as an underground sanatorium, is located on the 3rd level, in the Chambers: Wessel, Stajnia Gór Wschodnich, Smok and Boczkowski. Even when the extraction was still ongoing, the mine administration was developing underground tourism – especially following the modernization of the tourist route, and after opening the underground exhibition of the Cracow Saltworks Museum in the 1960s. The mine started to be visited by schoolchildren, labour leaders of industrial plants and delegations from ‘brotherly socialist states’. Two of the factors playing large role in increasing interest in the mine and its attractiveness to tourists were its inclusion in the registry of monuments in 1976, and later on – in 1978 – in the First UNESCO World Heritage List. When the Polish political system changed in 1989, and the country became a popular destination for foreign visitors, a real golden age of tourism began, and continues to this day. In 2005, the Wieliczka Salt Mine was visited by over 1 million tourists and in 2017 by 1.7 million. The visitors include members of royalty, heads of states, world-famous artists, athletes, actors and celebrities.

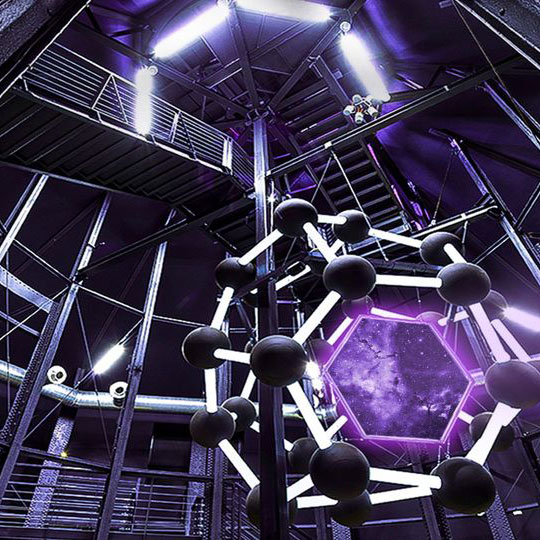

In striving to meet the visitors’ needs, the Mine and its environs constantly change: new themed routes have been set out underground, and the tourist route was made accessible also for the disabled. A number of workings has been repurposed with new functions – conferential, gastronomic, commercial. The Lill chamber now hosts state-of-the-art multimedia facilities (interactive applications, mapping, 5D cinema). Changes are also happening on the ground: the Regis shaft, with its extraordinary shaft top, was opened to tourists in 2012, following renovation. In the century-old brine baths of the St. Kinga’s park, a Grand Sal Hotel was opened, and from 2016 visitors and the spa clients can access a graduation tower – the largest in southern Poland.

Coal Mining Museum in Zabrze

The Coal Mining Museum in Zabrze is a cultural institution of the City of Zabrze, co-managed by the Local Government of the Silesian Voivodeship.

Zabrze is one of the cities that owes its civilisational advancement to coal mining. The first mine was established here in 1791, and after World War II the city was referred to as the "capital of Polish mining". It is no coincidence that the Coal Mining Museum, established in 1981, was located in Zabrze, initially as the only state museum of this industry in Poland. At first, it was subordinate to the Ministry of Mining, and from 1999 it began to operate as an institution of the Silesian Voivodeship. In 2013, the operating Museum was merged with the historic Guido mine. The Museum makes available to the public the tangible and intangible heritage of coal mining, and in particular the legacy of the two mines in Zabrze - the Guido Mine and the Queen Louise Mine, together with the Main Key Hereditary Adit, functioning under the common name of the Królowa Luiza Adit complex.

GUIDO MINE - A HISTORICAL OUTLINE:

The mine was founded by Count Guido Henckel von Donnersmarck, who received the mining grant in 1855, and the established facility was named after him. The mining field of the Guido Mine was then 1.03 km². Earlier drilling in the area suggested that this mining field would be rich in coal deposits, as was the nearby state-owned Queen Louise mine. At the end of 1855, Count Guido ordered the drilling of the first shaft, which was named Barbara. Soon, however, it encountered a dust pit and encountered a tectonic fault, which caused the shaft to be abandoned in 1856 after it had been sunk only 30 metres. In practically parallel, the drifting of the Concordia shaft (the name Kunstschacht appeared more frequently, but was eventually given the name Guido) was undertaken, in which the first mining level was soon established at 80 metres. Here, however, work also encountered difficulties due to tectonic disturbances, effectively hindering mining. In 1862, at a depth of 117 metres, the Concordia shaft broke the aquifer and work was halted. In the 1860s, Guido Mine was mining coal seams at a level of 80 metres. At that time, the Guido shaft was both a mining shaft and a dewatering shaft for the underground workings. In order to raise investment capital for its dewatering and further mining works, Donnersmarck formed a partnership with the Upper Silesian Railway Company (Oberschlesische Eisenbahn Gesellschaft). In 1870, the draining of the Kunstschacht (Guido) shaft began, after which further sinking of the shaft to 170 m was undertaken. At the same time, work was underway on the excavation of the mine's indispensable second shaft, which was named the Eisenbahn (Railway) shaft in honour of the new partner. In 1885, a record amount of coal was mined in the mine's history: 313,000 tonnes, but due to generally low profitability, in the same year Count Guido started the process of selling the mine to the Prussian State Mining Treasury (Königlich - Preussischer Bergfiskus) known as Fiskus. From then on, it was state-owned and, as the South Field, was incorporated into the state-owned Queen Louise Mine. The Guido shaft was dredged to a level of 320 metres and eventually reached a depth of 336.63 metres.

In the early years of the 20th century, a new mine "Delbrück" (later "Makoszowy" mine) was built to the south of the "Guido" mine, extracting coking coal. In 1904, the excavations of the two mines were merged underground and in 1912 the "Guido" mine was formally incorporated into the "Delbrück" mine. In 1922, after Poland regained its independence and Upper Silesia was divided between Poland and Germany, the two merged mines remained on the German side and became part of the state-owned "Preussag" concern. However, the mine staff remained largely in Makoszowy, which was allocated to Poland after the division of Upper Silesia. After the coal deposits were depleted, the former "Guido" mine lost its importance. In 1928, the Guido shaft was deactivated and the Railway Shaft ceased to function as a mining shaft. Instead, it remained a downcast shaft for crews and materials (an extensive timber yard was created in the vicinity). In 1979 it was backfilled to a level of 170 metres. The Railway Shaft, on the other hand, lost its function as an exit shaft and, until 1967, was only used to lower materials necessary for the miners' work and timber to bring in the mine casing. The area of the former Guido Mine was handed over to the Construction and Mechanical Plants for the Coal Industry in 1967. An Experimental Mine M-300 was established on the site, whose main task was to test new mining machinery and equipment. In 1975, the former South Field of the Queen Louise Mine was transferred to the KOMAG Central Design and Construction Centre. In 1982, an agreement was signed between the director of the M-300 Experimental Mine and the Coal Mining Museum in Zabrze. According to the terms of the agreement, part of the excavations were to be adapted for the purposes of an underground open-air museum. In the same year, on level 170, the Guido Mining Museum was created and opened to the public, later entered in the register of monuments. In 2000, in a wave of cost-cutting in the coal industry, the underground of the unique mine began to be dismantled. However, the involvement of many institutions, above all the Zabrze local government, the Marshal's Office of the Silesian Voivodeship and private persons led to stopping the decommissioning activities and establishing the "Guido" Historical Mine in 2007 as an independent cultural institution of the City of Zabrze and the Silesian Voivodeship. In the same year, level 170 was opened to tourists again, while level 320 was opened a year later. In February 2015, sub-level 355 was opened. In April 2013, the "Guido" Mine was merged with the Coal Mining Museum in Zabrze into a single institution called the Coal Mining Museum in Zabrze.

COAL MINING MUSEUM:

The nucleus of the Museum's collection was the salvaged part of the legacy of the Union Mining Museum in Sosnowiec, which existed between 1948 and 1972, and which was successively enlarged. An essential part of the collection is made up of technical artefacts representing the various branches of mining: excavation, dewatering, ventilation, transport, lighting, surveying, communications. Rich archives (with a unique collection of 18th and 19th century technical drawings) and geological collections (with a fascinating record of the „Carboniferous world” recorded in fossils and imprints) are also part of the museum's heritage. Another collection is the sphere of culture and tradition, illustrated by collections of miners' uniforms and insignia, exhibits related to the cult of the miners' patron saint, St Barbara, and ethnographic collections related to the everyday life of Silesian miners. Silesian and mining themes are represented in paintings, graphics and sculpture (including an extremely interesting coal sculpture), as well as collections of medals, beer mugs and musical instruments.

The objects belonging to the Museum are located in several different locations in Zabrze. These include underground facilities (more than 10 km of trails in underground coal pits with demonstrations of active mining machinery) and above-ground facilities (more than 30 facilities in 4 locations around the city - the Carnall Zone, Park 12C and the Military Technology Park). These are a variety of tour and experience options. The institution's offer is available regardless of the season or weather (no seasonality). A visit to the Museum allows one to trace the beginnings, development and decline of the coal age - as a symbolic reflection of the changes taking place across Europe.

Within the Guido Mine, you can visit as many as 3 mining levels (170, 320 and 355m) with still working mining equipment. A number of attractions are dedicated to thrill-seekers, e.g. the Mining Shift event (participants perform mining works 355m underground), or the equivalent of Shift for the youngest - Bajtelszychta. Adrenaline seekers will also find, for example, underground turbogolf, extreme running and laser paintball. Guido's unique offer also includes the K8 Zone - a modern culture, business and entertainment zone located at level 320 in the mine. It is made up of four huge chambers, enabling the organisation of educational workshops, training courses and scientific conferences, concerts and theatre performances, as well as culture and art fairs. A number of concerts are held here every year, e.g. as part of the Krzysztof Penderecki International Festival

THE QUEEN LOUISE ADIT:

The Queen Louise Mine was founded in 1791 and is one of the oldest mines in Upper Silesia. The Main Key Hereditary Adit, on the other hand, was built between 1799 and 1863 between Zabrze and Chorzów, and was the longest hydro-technical construction of its kind in Silesia. Its function was to dewater mines, make the deposit accessible and transport the excavated material.

At present the Queen Louise Adit complex includes surface buildings, modern infrastructure around tourism and two unique open-air parks. Today it consists of 3 main areas:

- The Queen Louise Adit Complex - the surface part around the Wilhelmina Shaft (Mochnackiego Street). This is the part of the Museum dedicated primarily to educational activities. Park 12C is a space where children and young people learn about the earth's elements, coal mining techniques and energy in nature. The Bajtel Gruba is a mini-mine, dedicated to children who learn about underground mining through play and teamwork. Military Technology Park - an opportunity to observe historical and modern military machines.

- The Queen Louise complex - the above-ground part around the Carnall Shaft (Wolności Street) In the surroundings of the Carnall shaft, a clear layout of mine buildings from the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries has been preserved, including the Chain Bath. Among the highlights is the historic steam engine - the oldest still operating such machine in Continental Europe. Visible from afar is the Carnall Shaft with its tower, on top of which there is a viewing platform. A number of exhibitions are also located in the Carnall area, including an exhibition dedicated to mine hazards and mine rescue, an exhibition dedicated to the history of mining electrification and mine lighting.

- The Queen Louise Adit Complex - underground tourist routes Due to the diversity of the mining excavations with a total length of over 5 km (consisting of the former galleries of the Quen Louise Mine and the Main Key Hereditary Adit), there are several variants of thematic and locational routes. It is also possible to take an underground boat trip along Poland's longest water route of 1,100 metres, which leads through a historic adit used to transport "black gold" in the 19th century. During the cruise, visitors will be greeted by characters from Silesian legends, such as the Treasurer and Utopek.

One of the buildings of the Coal Mining Museum is the former district governor’s office building at 3 Maja Street in Zabrze. It was erected in eclectic style in 1874. Its final extension of 1906 is the work of architect Arnold Hartmann from Berlin. The building has some of the most interesting historic interiors in the city, including the Stained Glass Room - the former assembly room of the County Assembly with a wooden polychrome vault.

In November 2022, the Pressure Tower - one of the tallest in the region, built in 1909 according to a design by architect August Kind - was opened to the public after a general renovation. An important part of the tour of the Tower is the permanent exhibition "CARBONEUM - the centre of coal knowledge" - a modern exhibition combining the functions of a science centre and a classical educational exhibition.

An integral part of the museum's activities is also its research and exhibition activities. Among the most important aspects of scientific and research activities, the protection of mining tangible and intangible heritage should be mentioned above all. This is where the Mining Documentation Centre plays an important role. Its main task is to collect, store and make available documentation obtained, among other things, from decommissioned mines. This task is particularly important in the context of the aforementioned restructuring of heavy industry and the social and economic changes taking place in Upper Silesia. The Centre's task is also to conduct extensive research and document valuable post-industrial sites together with their equipment and underground excavations. Caring for intangible heritage is a wide-ranging activity dedicated to the cult of St. Barbara, its protection, popularisation, and documentation. In 2018, thanks to the efforts of the museum, which coordinated the activities, the inclusion of St Barbara's in the UNESCO National List of Intangible Cultural Heritage took place. Currently, the museum has started its efforts for the inclusion of the St. Barbara celebrations („Barbórka”) in the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. In 2022, the museum coordinated the preparation and submission of an application for the inscription of the cultural traditions of the Upper Silesian mining brass bands on the National List of Intangible Cultural Heritage. The institution is thus one of the leading institutions involved in the protection and promotion of intangible mining heritage.

AWARDS FOR THE MUSEUM:

The institution is the recipient of numerous awards, the most important of which are undoubtedly the European Heritage Award/Europa Nostra Award 2019 for the Queen Louise Adit in Zabrze in the "conservation" category and the Gold Certificate of the Polish Tourist Organisation awarded in 2022.